Today, I want to share with you, probably, the most interesting conversation that we had up until today. Daniel May is a design professional, who’s been working with such companies like Sony and BMG, and it’s possible, that some of his works you can find in your music collection on the CD covers.

Nowadays, Dan shares his experience with students of the University of Nebraska, teaching design and I really envy his students, as Daniel is a magnificent storyteller and knows how to inspire people. Unfortunately, the plain text of the interview cannot share the atmosphere that Daniel creates with the help of his voice, manner of speaking, body language…

Behavioral psychology is one of Daniel’s secrets to success, that he shared with us during the interview.

Andrew: Could you please tell us some words about you and your experience?

Dan: I had started working in design after I’d been working in manufacturing for years. I graduated from school and I didn’t know what I could do with an art degree, so I started working regular jobs. I worked at a steel mill, drove a potato chip truck, hospital janitor, and worked on an assembly line for a car manufacturer.

I didn’t start working as a graphic designer until later in my life … my late 30s. So, once I started, I started from scratch – I started in production and worked myself up to designer… worked in a number of studios, worked for a package design firm that mainly did production work. Then, I moved into merchandising and promotions for a variety of companies such as Sony, BMG in the Chicago area. Then I’ve finally opened my own shop when I moved to San Francisco. I worked independently there for quite some time and recognized that a lot of the stuff that I experienced as a designer was not being taught in a university environment. That’s when I earned my MFA and started teaching. In 2007 I quit actively working in design. I mean, I still picked up jobs here and there when people contacted me, but not full-time. I was working this way until… 2011. That pretty much covers it.

Andrew: While working in this sphere, what was the most interesting for you, and what was the most challenging for you?

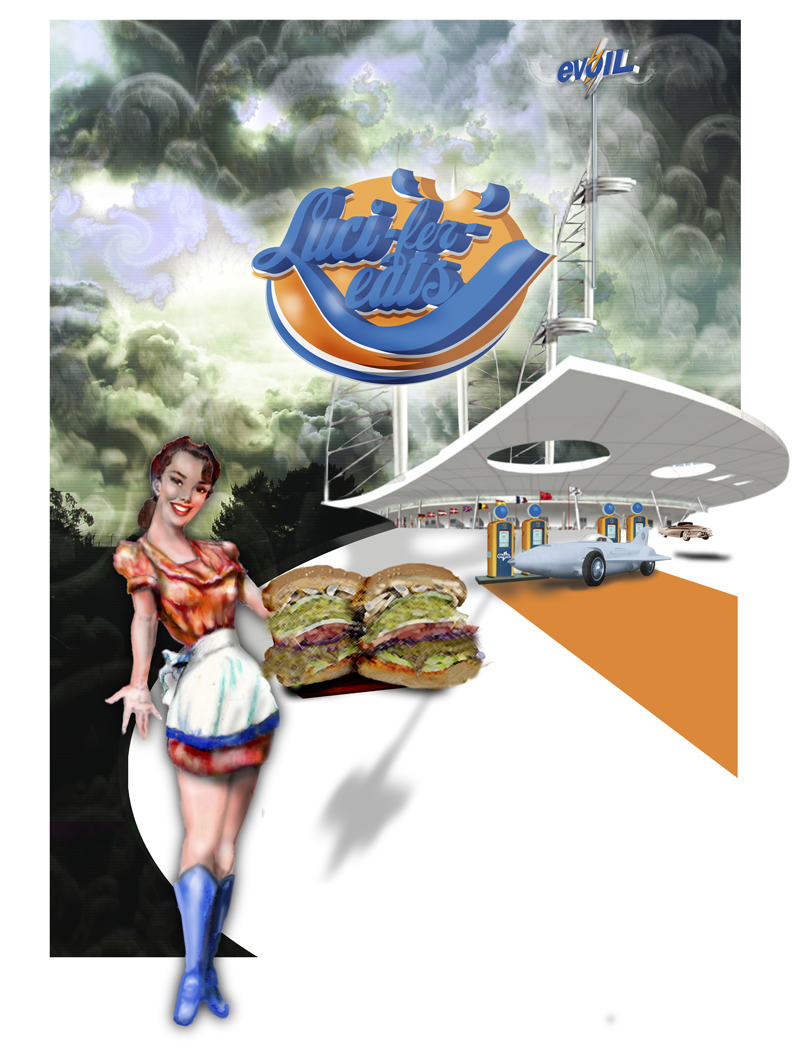

Dan: Doing the work is the most interesting for me. The creative challenges that it poses, especially, when I was working with entertainment clients… and sometimes in the packaging there were challenges too. Working with different types of materials in packaging, working with different parameters. Like I did packaging for food companies as well as doing packaging for merchandise companies, such as Walmart and a little bit for other smaller companies. So, working around that flexible material and trying to communicate possible avenues were the greatest challenges. Especially, when you are doing promotion of packages. I did a lot of work for musical artists and often they would want something that would be out of the ordinary – your poster, your CD cover, or something like that had to have some impact. So I tried to come up with some sort of package design that was interesting, or some object to place inside of the package would offer a lot of potential for creativity…touchpoints.

Andrew: Is there something special for you among your works?

Dan: I have a couple of things that I enjoyed doing. I did a pomade package for Stray Cats. This was a small metal canister that carries a hair treatment that had its logo on it with some pithy tagline. For those that don’t know what pomade is, it is what rockabilly aficionados put in their hair to keep it shiny and in place. There is a number of different types of things — chachkies, I call them, for the movie Kill Bill, that was fun to do. But as far as anything really stands out… I can’t think of anything that was particularly complex or difficult to do that stands out. They were usually very fun and simple.

Andrew: You had lots of jobs, worked in a lot of spheres. What is the percentage of time you had to work creatively? Not talking about processing processes but creatively.

Dan: Creatively, I would say was about 20%. Everything else, I would say, is 45-50% of production and process and then the rest is communicating with the client – either in the upfront process or during the actual creation after the design was accepted.

Andrew: Can you describe in general the whole process, starting with a new potential client appearance?

Dan: It took a little bit of behavioral psychology to communicate with some clients. You would gage it based upon how they smile, on their body language… Or, sometimes, a lot of communication was done over the phone, so you couldn’t gage it that way. So you try to recognize the voice inflection and things. Generally, we start with the simple thing that all clients do – is “all I want an XYZ object”. I’m trying to get them to pin down exactly THEIR idea of what this might look like. You don’t try to impose your own will on them, but rather let THEM tell you what they want. It saves a lot of time, cuts down on the iterative process when trying to funnel down or tunnel down what they really want. A lot of time and effort can be wasted just trying to find out what they want.

So, what I do is I try to do a number of little things. like I would say to them ‘’if this object is a human being, describe its personality, describe what it might look like.’’. Sometimes you can get little verbal clues and understand a little bit more about them (clients), their personalities, – what their likes and dislikes are. It’s important to let them be relaxed and understand that it’s a collaborative process and the only way it will work is if they’re willing to communicate with you. They should know that they are part of the process. You can bring a lot of creativity and fun to the object. The reason why they contacted me is because of my reputation in creativity. But I wanted to let them know that my hands are tied if they do not tell me the particular direction that they want to take. So that’s what I would do, I would ask them So if it is a human being, how would you describe that? And the way you can get a number of things can start from thinking about fun choice, you can start thinking about the personality of the actual product that you are designing for.

Andrew: Basically, you are trying to get brief?

Dan: Right. One of the things I tell to my students: there are a lot of companies you may work for that ask their clients to fill out a brief or they are sending marking people that do that for you. But if you are independent or a member of a small design studio that’s like a boutique studio, where I worked primarily, you are wearing a lot of different hats. So you should be ready to get this information yourself, what is that they (clients) really need. But the thing is, that they don’t know. They really don’t know until you show them something.

Andrew: Talking to other guys, I always ask about this approach how they get initial information from the clients.

Dan: In larger companies, a lot of them would have a design brief. But more frequently, I ran into the people that were wide open and they literally didn’t have any idea of what it was that they were trying to go for. They might have a general idea of what their target market was but in terms of what it might look like it was, sometimes, a little bit more… quite a bit more.

Andrew: And once he has this idea, you probably prepare some markups, some sketches. How many iterations\reviews did you need to accept the design?

Dan: Generally, what we try to do… What I try to do is to come to an agreement of acceptability for them. There is this little thing called Hick’s principle that says ‘’if you give someone too many choices, they cannot make any choice’’. So, what I try to do is to minimize that choice as much as I could by trying to say to them ‘’well this is what I suggest we start off with’’ and the most usual number would be 20 (number of offered designs). Sometimes, it went more than that. I tried to limit it to 20 because of Hick’s principle effect. I remember a particular instance where I worked on a logo project for someone and it lasted a month and I made over 1000 different logo variations (that was an exaggeration, but you get the idea), and it didn’t have any impact whatsoever. We just went back to the old logo and just shifted it around a little bit. It was a waste of time on my end and it was a waste of time on their end. They could have solved that problem a lot sooner if they had taken a little up-front time to think through what they wanted, or answered my questions honestly. They just did not get the idea that I was trying to help them by limiting the number of iterations they would have.

Andrew: Basically, we are discussing a period like 10 years ago, something like this, when the internet was not, let’s say, that widespread.

Dan: Yes, it was a little different. With the appearance of the Internet, I started to upload my works as PDFs and send them to the clients. But there were problems associated with that too because of differences in screens, differences in calibration of the screen, etc. I started envisioning possible problems that may occur in the future. And these are the types of problems that I teach my students now. Even though you may think or that client may think that a particular object is orange, it is only orange, or a red is red. That’s not necessarily true. Screen calibration can be a problem, but printing it on an output device that is not calibrated, and passing it around in the conference room might also affect it. With vision and color – you have all sorts of different variables that you have to deal with.

Andrew: Talking about the whole process of reviewing/approving the design, not just about colors but even places, shapes and so on. Right now, you have all those means that you can share – sent a sketch via email, write comments and discuss it. How complicated is to be on the same page discussing some artwork, discussing the sketch, while being in different rooms?

Dan: Even back then, like in the early 2000s, when I had clients that were in Europe and I was on the West Coast at that time. You were transferring information intercontinentally. It became sometimes challenging but I think the technology, even though it is crude by today’s standards, you could even send a JPEG, PDF, or screenshots using FTP or whatever. There were a number of different ways – workarounds, much more complicated than nowadays, but they worked. However, I was trying to explain them (clients from Europe) how something might work, how it (package) would appear in 3D space, of course, it was more challenging than today. I’ll be honest packages (talking about shapes) were very rare and that was the challenge. More often there were things like color than shape.

Andrew: The reason why I’m asking this is the tool we are working on. It is actually designed to solve the problem of approving and reviewing in terms of what we ‘need to change’, what ‘we like’, what ‘we don’t like’. The example, I am always using during the demonstration to potential clients, I have two pictures of interior design where I have a few couches in one place, a few tables in another place. Talking over the phone, you may say ‘’ok I don’t like that couch’’ but ‘’what couch? We have a few of them – the one on the right upper corner’’ – “Still, we have a few of them in the right upper corner”. This problem is quite a serious for the guys right now – the client means one thing, designers mean another thing and, at some point, they lose the idea. As a result, in the next iteration, the next version is incorrect and has wrong changes – not those, that the client initially wanted. Over the phone client says ‘’change this color’’ and in a month he says ‘’why did we change this color?’’ – to identify this “THIS” is the problem.

Dan: Yeah, I think that communication is the most difficult part of the job. It is about trying to be concise and trying to be as proactive as possible. It has always been a problem, even, for instance, when you are putting something in a 3D environment so it can rotate, and when you are using VR glasses where you can have a conference and then actually kind of experience what’s going on. I know that a lot of companies are working on that sort of experience, but I can still envision things going wrong and problems that are similar to the things that I experienced years ago. I think things will become more interesting… and less interesting since they will become less complicated. But I still think communication is a big part of the process.

Because if they misunderstand what you’re talking about … just as an example I had a client. There was a bank in Los Angeles at the time, and I was in San Francisco, so we were doing an identity project that had a broad array of items. And they kept talking about this color that they identified as a harvest gold. I had to come up with a plan to convince them that they needed to see a hardcopy proof of this color because to me it wasn’t a harvest gold at all. They gave me a more golden color and it was just orange, it was a completely different color, and I could only assume that it was based upon a screen representation of it. So, I don’t know if VR glasses have worked out the problems of calibration, but I could still see that same thing happening. You could be in the VR environment, someone is talking about a particular color. You say that you’ve got it and think that you’ve figured it out, and when the actual product gets to their shelf, they have a completely different experience. That can become, as you probably know, very expensive if you have chosen incorrectly, based upon a lack of communication. They might be loving something that you really don’t have any concept or idea of what is that what they see.

Andrew: How many people from the client’s side usually participate in making the decision in the proofing?

Dan: It is sometimes problematic, too. I tried to keep it no more than two people, but there were times when there were more eyes and hands-on than that, and that was making the situation more difficult. When you have more than one decision-maker, it really does become a complicated process of communicating between all of these people.

Andrew: Right, especially working with packaging or, let’s say, something where you have a marketing guy who says one thing, your legal department that needs some specific information, somebody else to proofread everything, and so on, and so on. How did you solve this problem of actually taking the information from these multiple people? You know, when someone has changed this and that, and it might cause losing something in the process or these changes can even be contradictory and etc.

Dan: Yeah, again, it’s kind of a delicate balance of trying to play out this. It’s kind of a psychological game by explaining everything to the clients and being as deferential as possible. For instance, you have to explain to them that you need one decision-maker to communicate with you as much as both of you can, because with too many people involved in the process, there are too many variables, and they’ll just add to cost. I found that if you spoke to them in terms of being very factual, being understanding, being empathetic, but also explaining to them that the more time you spend on a particular project, the more likely they are going to drive up their own cost. A lot of times, especially in a bidding process, when they would ask me to bid on a particular job, I would always have a clause that said that up to a certain point I would be as accommodating as I could. But if, for whatever reason, whether there was a disagreement on my end or disagreement on their end, there would have to be a change that we could both agree to…

And there have been times when accommodations could not be made, and I had to fire the client. In those particular cases I tried to explain to them that it wasn’t that I didn’t feel that we could do the job well. It was just that there were too many people involved, and it made it more complicated than it had to be, it was driving their costs up, and I didn’t feel that it was fair to them or fair to me to keep working on something that I didn’t see a resolution to. So there usually was this agreement defining upfront this number of changes you can make at the particular stage, and these many changes can be made at that particular stage. And if you go above that amount, the bid is no longer in effect, and it goes into an hourly… situation. If they were amenable to that, and if they were amenable to the fact that I called them a lot of times, then I would let it go as long as it needed to go. Because, again, after the interview process, I would generally draw up something that specified what the parameters were, where we were gonna go, how long I expected it to take, how many iterations each step I would allow, and then work from there. If they agreed to that then everything usually went well.

The clients that came back over and over again usually knew the drill, and I didn’t have to repeat it more than one time, but with an initial client I tried to be as honest, empathetic, and compassionate as I could be. But, at the same time, I tried to explain to them that this was a business arrangement, and they had to understand that they had some responsibilities as well as I had responsibilities. If they weren’t willing to meet those responsibilities, then it was best to just walk away at that particular time. There were a few jobs that I started off with people, who questioned that approach, and I didn’t get the work. There were other people with whom the process was going on for too long, and even though they agreed to the process, I didn’t see a conclusion, so we had to terminate the agreements. But for the most part, I would say 85% to 90% of the time, people understood the parameters, people understood where I was coming from, and it really proceeded pretty well.

Andrew: Talking about multiple people in the process. In our tool, we document every step, actually, to protect the design team. So, whenever the review is going on, a designer or a project manager sends the link to the client that he or she opens it in the browser. They see the mock-up, and all their change requests, all the annotations are drawn directly on this mock-up. You see every step and who was the person adding the annotation or a change request. You can send it to multiple people, your clients can send the same link, and this consequent invitation is also registered. As a result, in the second or in the third iteration you will see the whole history, why it took so long, etc.

Dan: Yeah, I think documenting it is a great idea, and having everybody involved where there’s an interactive environment where they can make changes and actually write on the screen. If they have a tablet or something where they can say: “this is the exact object that I’m talking about”, it is a great idea, and I think it could cut down on potential problems in the future.

Andrew: Anything you feel you would want to improve in the process of communication with the help of technology? I heard about VR goggles, that’s true, but still, technology is quite expensive and difficult to use because even if you are a designer, you can draw a draft, but to model it in the 3D space and upload it to the system, you need a special computer guy who actually might be even more expensive than you are.

Dan: *laughs* Yeah, I totally understand that. There are problems associated with that. I think Adobe Creative Cloud apps – as much as I reluctantly endorsed them because they have had a long history of understanding design problems and everything, – they made it a little bit more interactive with PDFs so that you can make comments on PDFs, and you can be discussing things with people simultaneously with all the things being in a cloud-based environment. You can have a much more collaborative piece that way, and it makes it easier to work, especially over a long distance because they can look at the same project that you’re working on in real-time, and they can make comments on it in real-time, they can even draw on it in real-time so that you can see exactly what they’re talking about. So, I think those are great innovations. If the process that you were working on could incorporate some of those, I think the template that they have for our interactivity would be a good base to start from. If you guys are working on a new platform or new software package that can compete against Adobe’s packages, I think that would be fantastic.

Andrew: Huh, thank you. Actually, about these things that you’ve just described … we do have everything! So, we can communicate live, and once we draw something, you would see it on your screen; but it’s not a package, it’s a web app. You do not install anything, you can just access the link from any device – it can be a computer, or it can be a tablet. So, you just navigate to the webpage, you see it, you discuss it in life, and once I type something in, you would see it right away. Plus, Adobe, as far as I know, is quite expensive, and probably you still cannot … I’m not sure about this, so probably it’s a question: can you invite some people who do not have the Adobe Clouds package?

Dan: That is problematic because if they don’t have the package, there are ways that you can create conferences that are based on Adobe Reader. Generally, most operating systems have some version of Adobe Reader with them, and then you just have to upgrade. But for real interactivity, sometimes you must have the person, at least one of the people within the group, who has an operating system. Now, from what I understand, depending on the system that you’re using, they do have trials that you can use for 30 days. I tell students: “when you’re working with a client who doesn’t have it, tell them to download the trial version for 30 days, and that way you can work out little kinks here and there”. Even if they want it just for a month, sometimes it’s as cheap as $50 a month and then they can get rid of it.

Andrew: Got it. As I said, that’s something that we’ve been working on. I know actually the market has lots of review tools that allow you to review artworks. It’s not totally simultaneous, not live, sometimes you need to refresh them. We’ve resolved that problem. But it’s interesting for us what other tools people are using. What other tools did you use professionally? For example, for managing your time, for managing the whole project. Did you use anything?

Dan: Well, I did have a very simple little app, years ago, that was nothing more than a time clock that I would click on and off. It was on my desktop. It showed me exactly how much time I was devoted to a particular project, and it would just compare and let me know if I was going over a time budget or if I was still within budget. That was the only thing that I really used that was based on managing my time, because, since I started off in the 90s when things were very analog, I just developed habits. But any app that would allow you to manage your time and then transfer that data into a spreadsheet of some type so that a client could use it as a guide of how much time it takes to do a particular project would be a nice thing. I just learned that back in those particular periods of time when I used my time app, I would just take all that information and transfer it over into a spreadsheet, and then I would put that spreadsheet into an invoice. That was the most tedious part of the whole operation – doing the bookkeeping.

Andrew: Actually, you’re not the first person I hear this information and this request from. We don’t have anything like this yet, but probably that’s something we need to add to our systems, thank you. Anything else you feel the modern technologies could help to solve? Any other problem you personally would like the technology to change?

Dan: Well, I think that it’s more of a behavioral change, and I think it’s a paradigm shift in the way people look at design. It’s starting to occur, but relatively speaking I don’t think that, especially in the arts, people have ever really given it enough credit in terms of how much respect they should offer the artists or the designer. It’s a much more intellectual process than just randomly throwing pixels at a screen, and I think that if generally people become more aware, and there’s no technology that’s going to do that, of how difficult this process is, I think that there’ll be more respect for the industry, and people will get more compensation for it. I think that for the most part designers and artists are underpaid, and the respect that they get is reflected in that in a lot of ways.

Andrew: Well, telling the truth, I personally think that modern technologies have changed that in terms of creating new tools and new software. You need to come up with some design that people would like, and previously that was like: “let’s put this in green, that in blue, and that’s enough”. Right now, I’m talking to the UX designers, UI designers, and I see how complicated that process is for them. They study the software, they create a picture of the potential client, and they put all the objects in it. It’s creativity, plus math, plus psychology, and so on, and so on, so it’s really complicated. It’s an interesting process, it’s interesting to collaborate, and it becomes more and more expensive. Previously, you could spend, like, ten dollars per hour to draw something, and it would be enough. It would take a few hours to draw one screen app. Right now, it takes like 30-40 hours just to make a research.

Dan: Many people still don’t recognize that. A lot of your work is done upfront in the research, and they think it’s all done on the computer screen.

I hope you enjoyed reading today’s blog entry. I know I repeat myself, but this conversation is one of my favorite ones, and I enjoyed every minute of it. Of course, it’s not everything that we discussed during this interview, but I traditionally skip my words about Approval Studio functionalities and their discussion. If you want to know more about Daniel May and his experience, let us know and we will try to arrange another interview to answer YOUR questions.

Feel free to contact Approval Studio team if you have something to share with our readers and have time for an interview with us. And, of course, I want to say thank you to all people, who read our blog and email us with their feedback, it’s important to us.

TEAM SOLUTIONS

TEAM SOLUTIONS WORKFLOW SOLUTIONS

WORKFLOW SOLUTIONS

REVIEW TOOL

REVIEW TOOL PROJECT MANAGEMENT

PROJECT MANAGEMENT TOOLS & INTEGRATIONS

TOOLS & INTEGRATIONS

CLIENT INTERVIEWS

CLIENT INTERVIEWS